The Americans’ foray into pirate-hunting came soon after Spain’s colonies began to agitate for independence after the end of the Revolutionary Wars (1801-15). The United States as we know it today would not have a standing navy until the 20th century. So when Spain-affiliated sea-raiders began attacking neutral American ships in the Caribbean, the American President James Monroe had a bit of a problem.

In the 1820s, American merchant ships were increasingly being targeted by Cuban pirates intent on defending Spain’s slave trade and economic interests from the burgeoning independence movement sweeping across Central and South America. But the US - comprised of the states of the eastern seaboard at this time - had few official naval resources and even fewer qualified personnel. They certainly had no experience hunting down pirates.

In contrast, the British were now rising to naval supremacy and were very efficient at this practice. The Americans had considered themselves the victors of the half-hearted war the British had fought against them in 1812. A mere ten years later, they were not about to let the British or the pirates get the better of them. Sending a handful of naval ships after pirates became a matter of national pride.

The venture met with mixed results.

The unfortunate Commodore David Porter

Commodore David Porter volunteered to lead the mission to destroy the Cuban pirates. He had just purchased a very expensive property in Washington for his wife and ten children and desperately needed the money to pay for it.

To be fair, Porter had his work cut out for him. Ships and personnel were in short supply. The US had only just acquired the Florida peninsula and it was woefully too undeveloped to act as a base of operations. Lacking fresh water and wracked with disease, many ships’ crews were felled by illness before they could set sail.

Porter was also his own worst enemy. Pompous and self-important, he immediately put the Cuban authorities – who were desperate to stop the pirates themselves – offside. Porter’s arrogance resulted in the Cubans refusing to allow an American ship to dock in Cuba. This severely curtailed the capacity of Porter’s commanders to resupply and hunt down pirates.

As the British Navy worked with the Spanish to efficiently track down and prosecute pirates, Porter claimed he could not find any. The US Secretary of the Navy grew increasingly exasperated with him. By late 1823, Porter spent more time carrying Mexican gold and escorting American ships for lucrative fees than he did pursuing pirates.

Porter’s inability to accept personal criticism caused him to be court-martialed for insubordination for an illegal landing in Puerto Rico. As a result, he was so disillusioned he became Commander-in-Chief of the Mexican Navy. He eventually accepted the consul-general-ship in Algiers, then a similar role in Turkey, where he died of illness in 1843.

Two of Porter’s sons went on to become distinguished naval officers in the American Civil War.

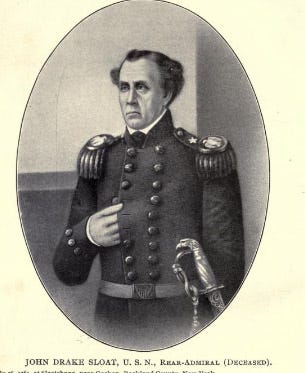

The success of John Drake Sloat

Lewis Warrington replaced Porter and proved far more effective at working with Spanish and British authorities. As Spain’s economic circumstances also improved, Cuban piracy began to decline.

However, there was still the problem of the pirates of Puerto Rico.

Born on 26 July 1781 and orphaned at a young age, John Sloat grew up in Sloatsburg, New York. The town was named after his grandfather. Around 1823, he was placed in command of the Grampus, an American vessel often tasked with naval missions.

Sloat was on his return from a slave-ship hunting trip to the West African coast in March 1825 when he called in to St Thomas, east of Puerto Rico in the Caribbean. There he heard of the large reward posted for the capture of whoever was responsible for a series of pirate attacks in the Mona Passage. Their leader was Roberto Cofresi, a notorious Puerto Rican pirate rumoured to have killed up to 400 seamen, including many Americans.

Sloat decided to lay a trap for the pirates.

With the assistance of the St Thomas Governor Von Scholten, Sloat obtained, manned, and armed two sloops to use as bait. In Puerto Rico, Governor Don Torre readily offered the assistance of some of his soldiers to help.

For weeks, the Grampus and its sloops cruised around the coast of Puerto Rico looking for the pirates. One day, while anchored at Ponce, on the central southern coast, they sighted a sloop off the harbour. The pirates had found them. The next day the Grampus pursued the pirates into the Boca del Infierno channel. A fierce and fiery engagement lasting 45 minutes ensued. Outgunned and outmanned, the pirates ran their sloop on shore and jumped overboard. Two were found dead, five or six were wounded, and ten were captured by Torre’s soldiers. Among them was Roberto Cofresi, the pirates’ captain.

Sloat brought Cofresi and his men to San Juan where Don Torre ensured their swift execution.

Aftermath

In 1844, Sloat commanded the Pacific Squadron and claimed Alta California for the United States on 7 July 1846. He landed at Monterey, took possession of San Francisco and within a few days, all California north of Santa Barbara was in the possession of the United States.

Sloat rose to the rank of Rear-Admiral by 1866 but his increasingly poor health kept him land-bound in his final years. He died at Staten Island on 28 November 1867.

He was survived by his wife Abby and three children.