Charles Johnson, mysterious author of a General History of the Pyrates, approached Ann and Mary’s stories in a way very particular to his time.

According to him, Mary Read’s mother married a seafarer. She gave birth to their son soon after her husband disappeared at sea. A short time later, Mary’s mother ‘met with an accident’ and found herself pregnant again, this time with Mary. When her firstborn baby son also died, Mary’s mother decided to disguise her new baby daughter as her firstborn son to somehow trick her husband’s relations into financially supporting her and Mary.

This set in motion the notion that Mary spent most of her life disguised as a male.

Johnson writes that it is through her male identity as a ‘man’ that Mary ‘grew bold and strong’, ‘developing a roving mind’. By the time she was around 15 she became a sailor, enlisting aboard a man-of-war. After that, she signed up as a soldier, serving with ‘a great deal of bravery’ in both infantry and cavalry units in Flanders. She then falls in love with another soldier, marries him, he dies, then she runs off to join the pirates.

Meanwhile, Ann was also born illegitimate in Ireland. Her father disguised her as the child of a relative entrusted to his care. He eventually took her to Charleston, South Carolina where he became a merchant and planter. Ann, writes Johnson, grew into a woman of ‘fierce and courageous temper’ not afraid to beat a young fellow who tried to rape her senseless.

The wilful Ann then ran off with James Bonny. According to Johnson, Bonny was a ‘libertine’, already married to a pirate named James Bonny when she took up with John Rackam and disguised herself as a man on his crew. However, a Jamaican Court later decreed her to be Ann Fulford: officially not married to either James Bonny, John Rackam, or anyone else.

Although historians have yet to verify the stories of Ann and Mary’s upbringing, there is certainly plausibility to them disguising themselves as men. Historians today believe there was a deeply-rooted underground tradition of female cross-dressing, especially in early modern England, the Netherlands and Germany. One observer in 1762 insisted there were so many women in the British army that they deserved their own separate battalions. Historians Dekker and van de Pol believed women did this for two primary reasons: to escape poverty (Mary) or to follow love and adventure (Ann).

Johnson’s portrayal of Ann and Mary’s stories perfectly fits the criteria for the ferocious ‘fictional female warrior’ stories popular at the time.

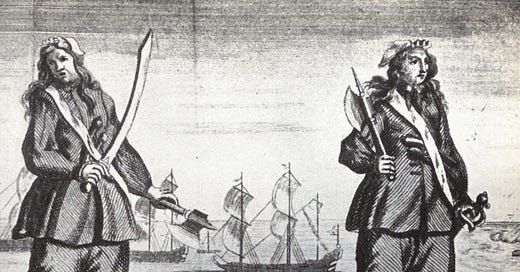

Instead of being mere equals, the women filled the ‘female warrior’ trope as the bravest onboard Rackham’s ship, ruthlessly fighting while the rest of the crew cowered below deck, or languished in their drunkenness. They cursed and swore. They carried pistols and machetes. They were sexually active. Johnson’s story of Ann’s sexual advances on Mary (who she believed to be a boy at the time) also fits the trope. Of course, after the two revealed themselves to each other and exchanged their secrets, any hint of romance dissipated.

It was still 1720 after all, not a porn film.

Some witnesses in their trial observed that Ann and Mary wore women’s clothes onboard the ship. This was deemed evidence of their acceptance onboard, despite their gender. Piracy historian Markus Rediker believed that Bonny and Read added an entirely new dimension to the subversive appeal of piracy by seizing what was regarded as male ‘liberty’. They clearly exercised considerable leadership aboard their vessel.

Yet despite Mary and Ann’s ferociousness as pirates, Johnson still needed to ensure their bloodlust was balanced by their devotion to a man: Rackham. While the ‘female warrior’ embodied the most masculine of values, the trope meant she must always remain feminine.

Up next: Ann and Mary’s portrayal in the book’s art