‘I am now to relate one of the most atrocious and consummate acts of piracy ever committed,’ wrote Captain William Bligh of the mutiny he endured at the hands of Fletcher Christian.

The 19 men loyal to Bligh managed to secure him a quadrant and a compass but all his navigational equipment, maps, drawing and money were lost to the mutineers. They also found some water and bread. As the mutineers drove the men one by one into a 23ft boat, a few pounds of pork and some cutlasses were thrown down to them.

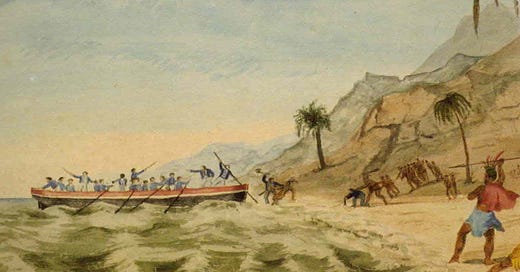

Dangerously overcrowded, the boat was cast adrift; and the men began to row away.

It took three days to make landfall at Tofoa, a dormant volcanic island in the Tongan chain. But there was little water available. Bligh then decided to make for islands where he knew the chiefs. But the wind and the stormy sea did not allow it. He managed to trade the buttons of their clothes with the islanders for coconuts and breadfruit.

This would be the last kindness the locals would show the castaways for some time. Within a few days, the helpful locals turned malevolent. Bligh and his men narrowly escaped attack, with one man killed as he tried to free up the caught stern rope.

Bligh quickly reassessed his options. He decided to try for Timor where he thought they could pick up a Dutch or English ship. But this was at least 1,200 leagues (more than 6,600 km or 4,100 miles) away, with very little food and in volatile weather conditions.

Nevertheless, the castaways’ attitude was to make their best effort or die trying.

Unfortunately for everyone on board the cramped boat, Bligh was not humbled by their predicament. Although he presented himself as a concerned commander doing his best in the face of adversity in his narrative of events, other survivor narratives, particularly that of John Fryer – who despised Bligh but who carried sufficient loyalty to Britain not to mutiny - presented Bligh in a far more critical light. Many of the officers openly blamed him for their predicament.

But there is no denying that Bligh’s navigational skill proved exceptional under the horrific circumstances.

As the boat headed east, Bligh managed to find a way through a gap in the Great Barrier Reef. He island-hopped on unpopulated attols and small islands with sufficient oysters and berries to keep the men just alive and rowing.

The boat cleared Cape York, the very northern tip of the Australian mainland on 2 June, just over a month after the initial mutiny. This heralded the beginning of the most treacherous section of the journey to Timor: crossing the open Arafura Sea. With no landfall, the exhausted and emaciated men came extremely close to starvation.

But then, they sighted Timor.

"It is not possible for me to describe the pleasure which the blessing of the sight of this land diffused among us," Bligh wrote.

On 14 June, the boat sailed into Kupang harbour and Bligh reported the mutiny to the authorities there.

But unfortunately, despite finally reaching safety, for many of the men, it was too late. Several died of malnutrition. By the time Bligh made it to Batavia to catch a ship back to England, he booked passage for only his clerk and his servant.

Everyone else either died or signed on as crew elsewhere.

Captain William Bligh returned to England a hero.

But what had become of Fletcher Christian and the other Bounty mutineers?