The Curious Case of Alexander Tardy

Recently, I spent a delightful hour debunking pirate myths with my former PhD supervisor. A great bugbear for both of us is always how centuries of pirate mythology has crept into the academic sources that feed Wikipedia. So unless people research, write and publish a whole new book debunking all of the myths and stories, the public information available about most pirates will remain inaccurate, faulty and on occasion, downright false.

He told me about how much he has learnt from the wealth of material he acquired on a Scottish pirate (who shall remain nameless) that Wikipedia states there is very little known about. Turns out he will literally have to write the book on that one.

I told him about a book manuscript I recently completed about the stories behind Somali piracy and all the weird people who got themselves involved in their hijacks. We agreed that despite 300 years between both sets of pirates, both our books talked about how sometimes, the people around the pirates were often far more interesting than the pirates themselves.

This caused the conversation to turn to a great example: Jacques Alexander Tardy. I gave him a brief mention in my book on Atlantic Piracy in the early 19th century. He was not technically a pirate, he just associated with them.

But he was a total psychopath and quite a fascinating character.

Pirates and phrenology

An article published by the Phrenological Society of Washington around 1834 is the primary source on Tardy’s story. Dr Brereton’s account drew on a newspaper article first published in the Philadelphia Gazette in July 1827 and a comprehensive report of trial proceedings pertaining to the piracy and murders on the American brig Crawford.

More on that later.

What is phrenology?

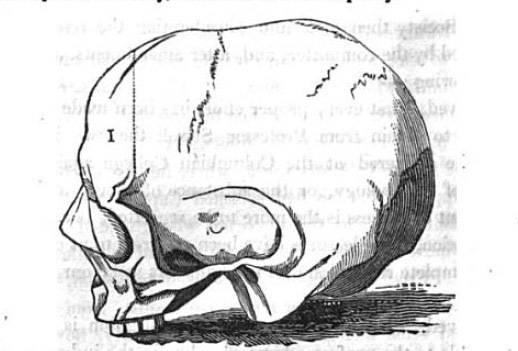

Phrenology is the belief that an individual’s character and psychological characteristics can be discovered by careful examination of his skull. In the pre-Victorian era, scientists considered it credible and intellectually respectable. By 1826, ‘craniological mania’ swept through Northern Europe. Models of skulls and busts were for sale all through London, phrenological books were bestsellers, and all phrenologists sought to add to their collections of skulls. Studying the skulls of criminals through phrenology was thought to remove the mystery of their deviant human nature and replace it with measurable and physical explanation for their actions. Phrenology quickly made it to the United States with accompanying scientific societies springing up in the major population centres.

In Alexander Tardy’s case, Dr Brereton performed the dissection of his skull. He concluded:

‘The brain is large; the mass situated behind the ear is enormously great; while the anterior lobe, the seat of the intellectual faculties, sentiments on accounts of the impossibility of representing the rounded form of the skull on a flat surface: the difference is very great.’

As far as Dr Brereton was concerned, Alexander Tardy’s propensity to poison people he did not like could readily be explained by the composition of his skull. That his work would be completed debunked within 20 years is not the point of this story.

What we do know is that, thanks to him, we have a comprehensive and pretty reliable account of what led Alexander Tardy into his life of crime and his relationship with three Spanish pirates.

Up next: Who was Alexander Tardy?